rb&h Arts Singing for Breathing programme and the singing participants at the Royal Brompton hospital 2017 and Liz Terry BLF trained singing for lung health leader and the Stroud 201 singing for lung health participants

by Phoene Cave

Introduction

My focus and specialism, for the purposes of this article, is Singing for Lung Health but I touch on other similar work. I have deliberately not named any individual or organization, but am hoping very much you will all respond and comment.

Leading Singing Groups for Older People

Guidelines published in 2015 by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence[1] provide recommendations for older people’s physical and mental wellbeing. These include access to a range of group activities and endorse

Singing programmes, in particular, those involving a professionally‑led community choir.

Who are these “professional” singing leaders? Where are they being trained? Are they being appropriately paid so they can support their ongoing continuing professional development? Who is defining what is “professionally-led”?

As the demand for singing groups grows, has it been considered who in the UK can call themself a singing teacher or vocal leader? There are fine lines between the amateur enthusiast, professional musician in healthcare, music therapist, and performing musician. Any one of these may indeed be an excellent, sensitive group leader with a large toolkit of repertoire and musical games, but how does the employer figure this out? Instinct is not a good enough basis on which to employ someone to facilitate singing, and time and resources are often too short to put in the research required. Without standardised accreditation it can be a challenge; both for those who want to find singing leaders and those who want to do the work. For potential practitioners, finding and shadowing good practice might be helpful; and an informed project manager with the time and resources to observe and evaluate sessions may be of benefit.

Singing leaders enter this work through diverse routes. The courses and training available to aid this process are equally varied. Leaders’ skillsets and backgrounds can vary from formally training to being self-taught, music readers, aural facilitators, and/or choral conductors. There are music and health and music therapy courses which welcome singers, but they are not specifically voice-focused. What I cannot find is one training in voice and vocal leadership skills which gives a thorough grounding. Nor can I find a central resource to inform existing and would-be singing leaders about the information and training available to further their professional development.

Singing for Wellbeing and Health

With the growing demand for singing for health and wellbeing groups in clinical and community settings, there is the added dimension of the singing leader needing to support often older, vulnerable participants with specific health issues, including mental health, Parkinson’s, stroke, dementia and lung disease. The expectation is to facilitate within music. It is no mean feat juggling the musical elements of tempo, rhythm and pitch within a structured yet responsive session. To commissioners, it may be “just a sing-song” but moving body, breath and voice can be powerful physically, emotionally and psychologically.

I would suggest that this work is more complex than it first appears. Are there sufficient numbers of skilled facilitators to meet the increasing demand?

If there is a push for robust evidence-based outcomes so that more groups can be funded and sustained, then do we need to highlight the importance of ongoing training, supporting and paying this workforce appropriately? If we are measuring participant outcomes, then do we also need to evaluate delivery and content?

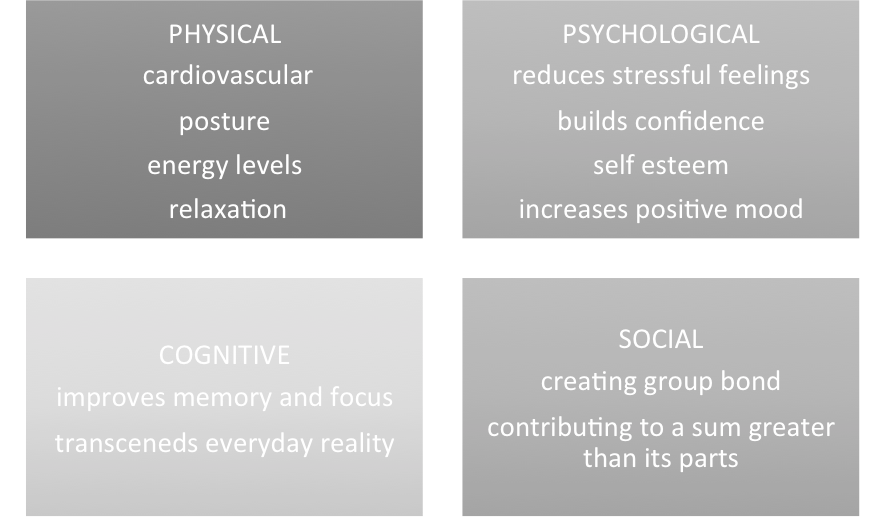

We know from Clift, Hancock, Staricoff and Whitmore’s 2008 review[2] that singing in a group impacts on four main areas:

Introducing participants with a specific mental or physical need and the picture makes it more complex. Take participants with lung disease, for example:

Severe breathlessness changes the breathless person’s psychology, horizon of possibility, sense of trust, capacities and embodied subjectivity. It transforms the breathless person’s relationship to her world, to herself and to others. It changes how she views herself and what sense of agency, possibility, and physicality she comports herself with.[3]

Our breath is invisible until our breathing mechanism starts to function less well – there is something about holding, pushing, moving, grabbing, snatching or extending the breath that requires different skills from the singing leader than working with specifics of speech or movement in a group with neurological issues such as aphasia or Parkinson’s disease.

Some groups for those with chronic lung disease offer support for better breath management:

The learning of techniques around breathing control and posture that are necessary to sing effectively is combined with a group activity that is perceived as fun and sociable. The goal of the groups is to become able to produce song, an artistic objective, but through this process individuals acquire skills to help them to cope with their lung condition, a health-improvement objective.[4]

As breath powers phonation, it also makes singing a very appropriate intervention. And yet,

Breath is so fundamental to us and yet so invisible an entity that any discussion or examination of it can send some people spinning into instant confusion or panic.[5]

Participants need to learn to regain voluntary control of the breath, using greater and more appropriate muscular activity to support a sung exhalation than a spoken phrase. Issues with vocal cord dysfunction can add further complications, and more than half of people with COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) have co-morbidities (other co-existing medical conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes or depression).

Some participants choose to attend for the distraction of a good old singalong, and do not want to take an in-depth look at ingrained habits that may be exacerbated by their diagnosis. They may continue to sing with poor posture, poor breath and unhealthy phonation. How might this impact on the less experienced singing leader who may not pick up on this if they are under pressure to produce certain outcomes? Informal responses from the group may be excellent, but research results may be poor. This may also be down to how the outcomes are being measured. Spirometry tests are one of several ways to measure lung function.[6] (I do sometimes wonder how well the words ‘measure’ and ‘arts’ go together, but that is for another time).

It can be just as confusing for new participants looking for a group to know what the focus is, working on an assumption that all groups offer the same thing, which is of course not the case. Some participants are very clear they want support with their breathing, with singing as the tool to do this:

…when you’ve got a chronic condition support is actually quite important I think – you know and I think what this course gives you is the ability to help yourself … there is [a singing group] that is a 10 minute walk from me but I think it is more or less just a singalong really and I do want to go to a singing for breathing group because all I will do if I go to the just a singalong one is continue my same bad habits, so you know – it will be fun you know, but it won’t actually improve my breathing.[4]

I would suggest that the complexity of this work extends across participants, hosts, singing leader and researchers. I also suspect there will be similar issues in other singing for health settings.

Participants

Desires: Education, enjoyment, distraction, creative experience, social connections; to learn new skills (both physical and musical), make new friends, feel more in control of their breathlessness, move, relax, find an emotional release and have a “good old sing”.

Challenges: Self-awareness, behavior change, self-confidence & self-esteem, singing, dysphonia (or other vocal dysfunction), funding, sustainability, group numbers, transport.

Hosts

Desires: All of the above, plus positive feedback via stories, pictures, video and performances to indicate success.

Challenges: Safe practice, supervision, sustainability, embedding ongoing evaluation.

Researchers

Desires: All of the above plus making a clear distinction between advocacy and evaluation. A robust randomised controlled trial. Standardised questionnaires recognised within the NHS.

Challenges: Qualitative? Quantitative? Mixed methods? What and how to measure the complex interventions? More research is needed on how we breathe to sing. How do researchers satisfy conventional research methodology for lung function whilst capturing the entirety of this holistic intervention?

Singing Leaders

Desires: To learn as much as possible to be the best they can, get subsidised continuing professional development (CPD), be within a support network, and receive more practical support setting up groups, mentoring and supervision.

Challenges: All of the above!

I would suggest that those who facilitate singing for wellbeing and health groups should have access to high quality and diverse training in this country if they want it. Not everyone will. If groups are being set up to work with specific health needs with an expectation of certain outcomes, however, I would suggest that it is needed.

I believe that many singing leaders would benefit from fully rounded training in voice and vocal leadership prior to even entering the healthcare field. A course that would equip singing leaders across education, community and healthcare settings, which welcomes leaders from whichever musical or singing environment they come from.

There are Masters courses emerging in vocal pedagogy, and others in community music – why can there not be one place, one course which offers all of it in modular form so participants can pick and choose – i.e. a fully rounded training that enables singing leaders to have a thorough understanding of how the voice works and potential vocal dysfunction issues, posture, anatomy, body, breath, as well as all the elements of group facilitation and musicality? (Accreditation is an ongoing, contentious issue and not one for this article.)

Is it unreasonable to ask that burgeoning and blossoming singing for wellbeing and singing for health groups get the best possible facilitators? There should be choice about how people learn – some will not want formal training and others may wish to learn through an apprenticeship model. Both should be valued and supported, and partnership and peer mentorship embraced across the board.

Participants in specific Singing for Health groups (as opposed to more generic, but equally important Singing for Wellbeing groups) deserve access to a community-based, fun, musical session with a singing leader who not only has experience of working with vulnerable participants but also understands the basics of vocal production (it is a singing group after all) – which also means they can be safe in the knowledge that vocal dysfunction issues will be acknowledged, managed or referred on. Participants deserve an enjoyable session that embraces the social, cognitive, physical and psychological, as well as the complex needs associated with their diagnosis.

Hosts deserve to have access to competent, inspiring singing leaders (and to know where to find them).

Researchers deserve the time and money to develop appropriate research methodologies from a broader skills base than “the usual suspects”. The research should be both robust and deep (i.e. reflecting the depth of participants’ experience). This arts-based intervention also deserves to be taken seriously by those who fund research. Researchers deserve support to assist participants and hosts should fully engage with the research process for best practice and best results.

Singing leaders deserve access to a fully rounded training programme on the myriad components of voice and voice leading (before they even access further training connected to participant diagnosis). Singing leaders deserve decent fees so they can continue to invest in their own CPD.

I leave you with an important quote from a Singing for Lung Health leader as I ponder further how we could help support a) more participants to embrace the potential of self-management, self-awareness and behaviour-change within a singing session whilst having a really good time; b) singing leaders to gain the skills to facilitate to the best of their ability; c) hosts to find a skilled workforce, to evaluate and fund appropriately; and d) researchers to have the time, funding and interdisciplinary skills to choose appropriate measures.

Participants gradually lose self-consciousness and gain self-awareness. We do not forget our bodies and our breath, but they are not the primary focus, they are the means by which we produce sound.

For people with lung health conditions, the breath is often a barrier to living. When we sing, the breath enables creation of something new, promoting life not inhibiting it.

It is the barrier that is forgotten, not the breath.

Phoene Cave worked in the television and record industries before becoming a professional jazz and pop singer. She has a BMus (Hons) from London’s Goldsmiths college and a PG Dip in Music Therapy from the University of Roehampton. As well as being an HCPC registered music therapist, she is also a qualified shiatsu practitioner registered with the CNHC. She has spent the past two decades working with communities in schools, nurseries, concert halls, social housing, further and higher education colleges and universities, hospitals and prisons. Phoene has facilitated singing and project managed across areas of performance, education, community music, music and health and music therapy. She has worked as a practitioner, performer, manager, consultant, lecturer and trainer and is passionate about the creative connections between music and wellbeing. https://twitter.com/omphoenix. www.phoenecave.co.uk

The author is writing in a personal capacity. The views contained in this article do not necessarily reflect those of LAHF or the organisations described therein. Copyright is retained by the author.

[1] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng32

[2] Clift S, Hancock G, Staricoff R, Whitmore C. 2008. “Singing and Health: summary of a systematic mapping and review of non-clinical research”. https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/health-and-wellbeing/sidney-de-haan-research-centre/documents/singing-and-health.pdf

[3] Carel, H. 2016. “Phenomenology of Illness”. https://lifeofbreath.org/2017/01/a-phenomenology-of-illness-part-2/

[4] Lewis A, Cave P, Stern M, Welch L, Taylor K, Russell J, Doyle A-M, Russell A-M, Mckee H, Clift S, Bott J, Hopkinson NS. 2016. “Singing for Lung Health – a systematic review and consensus statement”. Available at http://www.nature.com/articles/npjpcrm201680.

[5] See above.

[6] http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/spirometry/Pages/Introduction.aspx

This article makes an excellent point. As Phoene says, this kind of work is far from just a good old sing-a-long. Song leaders are expected to be fully cognisant with the singing process, the breathing technicalities, the mechanisms of producing sound (in just the same way as Speech and Language Therapists might also be), as well as be able to ‘hold’ a diverse group, which may have participants with mental health needs; be self-managing a chronic illness; have historical voice use or posture problems; come with whatever baggage makes us fully human. They then need to have business skills; be adaptive and flexible; be resourceful, and a host of other skills. There is no current training which meets all these demands. Singing is increasingly recognised as something which has massive health and community benefits. Surely we should take this seriously, and seriously empower those in a position to teach and to learn?

Wow what an inspirational blog!!

I have found the same thing…most of my training is experiential but it takes years to build and when I first started facilitating art, music and drama workshops with vulnerable people from all walks of life, I often wished there was someone I could turn to, or some structured programme whicb would help me deal with trying to provide both the nurture which Arts in Health calls for, alongside creating a quality opportunity for participants to develop their arts skills…and working to be inclusive and prevent barriers which could be caused by issues such as autism, EAL, alzheimers…homelessness…trauma…etc…

This year I was asked to provide open training workshops for the Birmingham arts charity I work with and for all the reasons you outline so cogently I will deliver sessions aimed at anybody who wants to facilitare any form of arts workshop and might be unsure where to start…it’s not the degree you call out for…but I guess it’s a small response.

I thought I was the only person recognising this problem, but you have brought it into the spotlight…thank you…I hope changes develop from here onwards.

Hi,

If you’re interested in using choirs or music generally as a way to help people learn about health and well-being go to http://www.sexanddrugsandrockandhealth.com/Further%20exploring%20using%20story%20and%20musical%20SPOTIFY%203.pdf .

There is a summary of ideas on page 41 and tips on how to access the accompanying Spotify playlists on page 10.

Just want to recommend the following organisation who would have a wealth of experience in developing appropriate and accredited training for community dance practioners and would have dealt with many of the issues mentioned.

http://www.greencandledance.com/

Maybe worth contacting

I was fascinated to read this, as I’ll be training as a Singing for Lung Health workshop facilitator next month.

I find it a great privilege to work within a singing for wellbeing field currently, and am awaiting the great new challenge of transitioning into this more specific role focusing on singing for health.

Ongoing professional development can be difficult to prioritise, since it is often overlooked and work can be underfunded. This important field of work certainly seems to be gaining momentum as results become apparent, and I can only hope that greater research studies will push things further yet.

A fantastic blog – each point well made and very well founded! We need to keep these discussions alive to get the recognition needed (to then hopefully turn that into some decent funding and resource!)

A very interesting piece echoing much of our experience of delivering Singing programmes for people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and other Long Term Conditions here in Tayside. Certificated training may be valuable but may also generate unrealistic expectations as it will not address the fact that there is little sustainable resourcing for this work (or the majority of participatory Arts in Health work). Trained professionals for a resource poor sector!

Thoughtful blog post Phoene! I applaud the idea of a modular course. Surely there is an entity out there that would be prepared to take it on? If not, somehow those of us who are passionate about training/facilitating/healing through the voice need to get together and create it ourselves.

Thank you very much to everyone who took the time to read this article and to respond. The interest shown means I will progress and send out questionnaires to a broad section of singing leaders to see if there would be interest in a training course which I would then set up and put in a funding bid to subsidise some of the costs. This was never my intention when I started to write but is clear to me now is needed. I feel that Singing for Health, beyond the generic ‘sing-a-long’ is going to keep building and there is a danger that we will run out of experienced singing leaders, or they will all live in the same areas. To lead group singing well (especially for those who are vulnerable or with additional needs) it needs to look very easy and therein lies the misunderstanding – your feedback has been invaluable and very much appreciated.

I have long been an admirer of the work that you do, Phoene. Thank you for your post here. You address a very crucial issue and that is how do we best equip those who facilitate healthy singing in people with respiratory ailments? Thus far, there is relatively little information available outside of academic journals, which are not always accessible to most music teachers. I strongly believe that lay resources, including practical training courses, are necessary to support this growing field. As you say, singing for respiratory health cannot simply be a “sing-song.” Attention must be paid not only to the students’ posture and breathing apparatus but also the actual vocal output, especially since many of the issues related to dysfunction in breath support result in a dysfunctional sound. This can be difficult to monitor in a group setting. A good song leader will have training in vocal pedagogy (the art of teaching) and have many tools to assist in their teaching. This leader must also have experience with the aging voice and vocal health issues. Furthermore, a solid understanding of the presenting medical issues is necessary to tailor breathing strategies, musical and physical expectations and any recommendations for practice. I do not know whether this is the domain of the music therapist, who is usually licensed, or the voice teacher, who could be anyone. I suspect that in the future we will see a need for certification if funding is to be obtained. I do know that it is a likely scenario that a respiratory patient would hear via various sources (social media etc.) that singing is good for your breathing among other things. This patient is then likely to seek an opportunity to sing, whether that be in a private singing lesson, a choral setting or a singing group, as you have in the UK. In my mind, good teachers are always looking for information to help their students with their unique needs. Thus, it is so important that resources be made available. I am so pleased there is a training program through the British Lung Foundation. I do hope that continues and that as more people catch on to the health benefits of singing, more training is obtainable. Thanks for all that you do!

Thank you for blogging about this. I have recently started running a “Singing for health” group and I am desperate to undertake some specific training. I live in Guernsey and so am willing to travel for this but haven’t been able to find anything. It’s very frustrating! I look forward to hearing more and will continue to search out training opportunities.

Hi Sammy – the BLF are running a free course next month for existing leaders! The deadline is past but if you can get back to me in the next 24 hrs I can send you the details and worth applying – there will be another next year – email me at phoene@phoenecave.co.uk and Mayana at singing@blf.org.uk